Image source: The Guardian

If you are reading this article, it is likely you are a parent of, or carer for someone with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), or another related condition.

As such, many professionals will have suddenly appeared in your life as they run assessments, ask you to fill in questionnaires and interview you and your child in order to deliver a diagnosis. But even after a diagnosis, it is not often clear what the treatment options are.

Through the process of seeking out options, you are likely to come across ABA (Applied Behaviour Analysis). For practitioners and families alike, discovering ABA can be a life- and career-changing moment.

I recall my own story quite vividly - sitting in my final year undergraduate psychology course, I had become disillusioned with the psychology I had been learning for the past two and a bit years. I felt a lot of the concepts and constructs were “fluffy”, subjective, and difficult to validate scientifically. I originally went into psychology because I wanted to see it applied in a scientific and objective way, but I'd found very little of this in my course.

My first lecture on ABA sucked me in immediately. Here was a scientific approach to behaviour, rooted in objective data collection, with 50 years of empirical research and a wide-ranging application. Yes please.

Below, I look at ABA in more detail, thrash out some its core principles, and clarify some myths and misunderstandings about the discipline.

ABA – what’s it all about?

ABA is a scientific approach to the understanding and improvement of behaviour. It is outcome-focused (which means we look at what changes are possible and identify strategies to bring about those changes), with an emphasis on achieving socially significant change (changes that make a meaningful difference to the young person and his/her family). It can be applied in a variety of ways, including for individuals with learning disabilities, in organisational behaviour management, for individuals with dementia, as well as sports performance and addictions. Key terms you’ll come across when looking at ABA include:

Function based

- A behaviour analyst focuses on why the behaviour occurs rather than solely on what the behaviour looks like (the functions of behavior). By identifying “why”, behaviour analysts can implement proactive strategies based upon an antecedent (or what happens before a behavior) that teach the person socially significant replacement skills generalised across people, settings, and time.

Person-centered

- Each ABA programme and intervention is individualised to match the skills and deficits of the individual, and is designed with motivation at the forefront to achieve socially significant behavioural change.

How does it work?

In essence, ABA focuses on reducing negative or socially undesirable behaviour whilst teaching replacement skills and strategies that equip the individual to live a more independent and socially engaged life.

Because ABA is a scientific approach to the understanding of human behaviour there is a heavy emphasis on data collection and data analysis. Data is collected on behaviours of interest, be it how often a behaviour occurs (frequency), for how long (duration), and/or under what specific conditions (ABC data). ABC data records the Antecedent, the Behavior (the actual response), and the Consequence (what the behaviour results in, i.e., what maintains the behaviour). It is with these data that decisions are made about behavioural interventions and skill acquisition programmes.

Given that ABA is individualised, socially meaningful change is different for each person – for one individual, it may be learning to make a snack independently, for another it may be around community life skills such as following shopping lists and paying with correct money, and for another it may be establishing a communication system that other people can understand. Skills are broken down and taught in small, teachable components, adapted the individual’s abilities.

What does an ABA therapist do?

ABA practitioners may hold varied job titles – ABA tutor, ABA therapist, behaviour support therapist (BST) and instructor can all be used interchangeably to describe behaviour analysts who are mainly responsible for programme implementation. In other words, it is the primary role of the ABA therapist to work directly with the individual, implementing behaviour support plans, task analyses, and skill acquisition programmes, whilst taking data on behaviours of interest.

The ABA programme is typically designed by an ABA supervisor or consultant in collaboration with the ABA therapists who see the service user on a daily basis. The programme should be designed after initial observations and baseline assessments, which identify core areas to target as part of a treatment programme.

ABA supervisors oversee implementation, analyse data collected to make data-driven decisions, facilitate training, and may overlap with ABA therapists to ensure consistency and professional development. In addition, it is typically the role of the ABA supervisor to be the point of contact for parents and external stakeholders, such as social workers (though this is case dependent).

How does ABA therapy work for autism?

One of the most widely recognised applications of ABA is the work that is being done in the field of autism. There are over fifty years of empirical research evidencing the efficacy of ABA for individuals with a diagnosis of autism.

It is important to highlight that ABA is not used to “cure” autism – autism is a lifelong developmental disability. The focus on an ABA intervention for an individual with a diagnosis of autism is therefore not on curing autism, but rather on giving the individual skills to live as independently as possible.

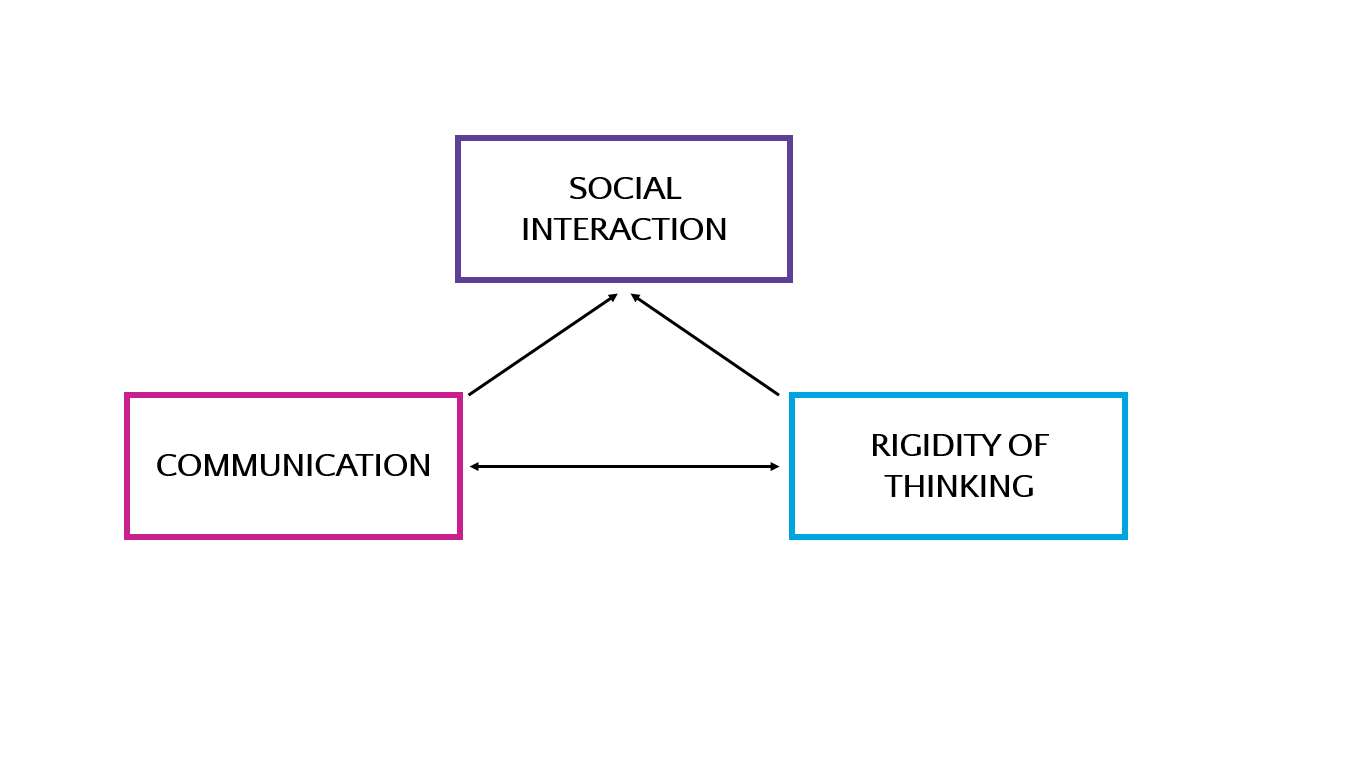

Autism is characterised by a triad of impairments – communication difficulties, social interaction difficulties, and restricted and repetitive behaviours/interests. It is where the deficits are within this triad of impairments that behaviour analysts target as part of an ABA programme.

The focus is often on establishing a communication system that works for the young person - spoken language may not be possible to teach initially, and an alternative mode of communication, such as sign language or PECS, may be more appropriate to introduce.

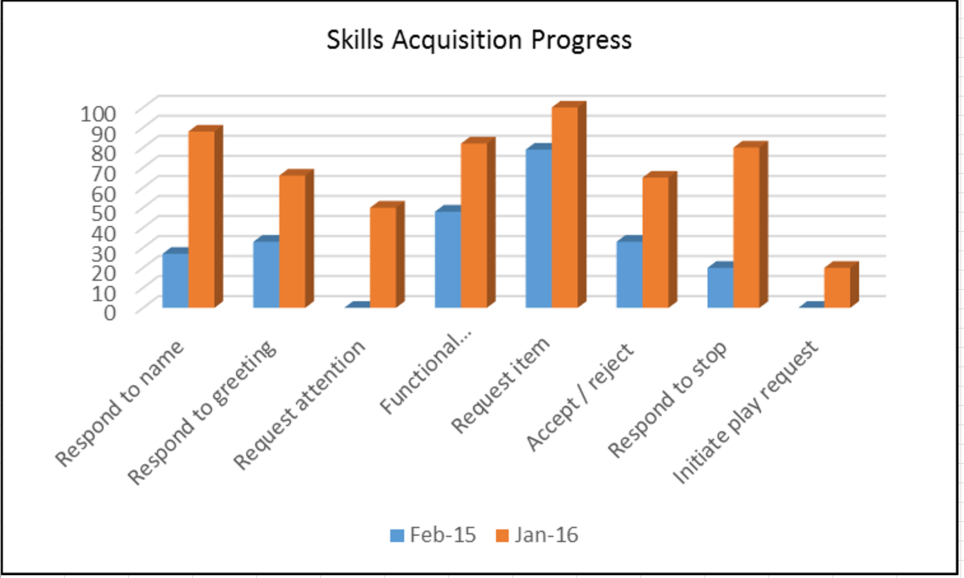

Other target areas may include turn-taking, imaginative play and self-help skills. Each ABA programme is individualised to the young person’s assessed needs, with treatment plans formulated after assessments have been completed. Daily data collection and subsequent analysis guides clinical decisions related to the programme.

COMMON MYTHS SURROUNDING ABA THERAPY

MYTH 1: ABA is an unregulated industry

There are decades’ worth of research articles to demonstrate the effectiveness of ABA in establishing positive behavioural changes (two of which can be found on our useful links page).

The focus is on an individualised, data-driven, person-centered programme that breaks tasks down into small, teachable units. However, it is important to be aware that ABA is only effective if implemented correctly.

Unfortunately, until very recently, the field of ABA had been unregulated in much of the world, so that anyone technically could claim to be an ABA practitioner but this is changing. The Behaviour Analyst Certification Board (BACB), which oversees the field of ABA, has documented best practice and ethical standards, and has introduced formal qualifications and accreditations.

The BACB exists for behaviour analysts to register as certified practitioners. There are a number of credentials that BACB oversee - Board Certified Behaviour Analyst (BCBA – which can be upgraded to BACB-D for those holding a PhD qualification in addition), Board Certified Assistant Behaviour Analyst (BCaBA) and Registered Behaviour Technician (RBT).

The BCBA credential is the Gold Standard within the field of ABA, and as such, it is recommended that any ABA programme is overseen by a BCBA. The RBT is an entry-level credential which is relatively new – going forward, all ABA tutors/behavioural support therapists should hold this credential or be working towards it.

With these formal qualifications now being required more frequently, it ensures that an ABA programme is implemented by trained professionals, who use evidence-based practice to bring about behaviour change.

MYTH 2: ABA is the same as VB

ABA is the scientific approach to the understanding and improvement of behaviour. Within the umbrella of ABA, there are a number of approaches that differ in philosophy but use the same underlying principles. Such approaches may include discrete-trial training (DTT), verbal behaviour (VB), and natural environmental teaching (NET) to name but a few.

Many ABA programmes do not subscribe to a specific “type” of ABA application and may instead use strategies from each to form the basis of a programme. A core distinction between VB and “typical” ABA therapy is that VB focuses on the teaching of “verbal operants” (e.g., mands [requests], tacts [labels], intraverbals [conversation exchanges] etc.) – work that was originally introduced by B. F. Skinner. Put simply, VB could be described as the application of the scientific principles of ABA to language.

However, this simple description may suggest that other teaching methods used within the field of ABA do not focus on language acquisition - this is not true. ABA focuses on function-based intervention. Often, the replacement skill that is taught is a functional communicative system that can be established and maintained using a variety of teaching strategies that fall under the umbrella of ABA.

MYTH 3: ABA uses punishment to control behaviour

While it is true that some historical, and much-publicised, ABA programmes in the 1950s and 60s used aversives (or punishments) to decrease problem behaviour, 21st century ABA focuses on person-centred, antecedent-based strategies to motivate change.

It is important to clarify that “punishment” is a technical term in ABA that differs from everyday conceptions. Punishment procedures in ABA refer to strategies designed to decrease the likelihood of a behaviour occurring in the future. When you hear the term “punishment”, it may conjure images of shouting, slapping, use of aversives, etc., to punish a behaviour. To be clear, punishment procedures routinely used within ABA are nothing like this. Withholding/delaying reinforcement, reducing amount of time spent on activities, etc., are simple but effective punishment procedures that may be used by practitioners.

Behaviour analysts are bound to the BACB Code of Conduct, which advises, “The behaviour analyst reviews and appraises the restrictiveness of alternative interventions and always recommends the least restrictive procedures likely to be effective in dealing with a behaviour problem.”

A soundly designed treatment programme that is function-based need not rely on any use of punishment: Proactive, antecedent-based strategies matched with potent motivators is often sufficient to bring about significant positive behaviour change. For example, teaching an individual a new communication system, providing consistent reinforcement contingent on desirable behaviour, offering frequent opportunities for breaks, and providing choices across a young person’s day can be highly effective in teaching new and important skills.

MYTH 4: ABA is similar to dog training

Repetition is an important part of learning for individuals with complex behavioural needs – with the aim of acquiring skills to a level of proficiency that these can be generalised across contexts and individuals. However, such “repetition” is often characteristic of only one component of an ABA programme - discrete trial training (DTT). A well designed ABA programme should use a variety of evidence-based approaches, including DTT, natural environmental teaching (NET), incidental teaching, and fluency based instruction. In my experience not subscribing wholly to a singular approach within the field of ABA allows for more flexibility to individualise programmes.

MYTH 5: ABA programmes need to be 40 hours a week to be effective

Research has found that intensive ABA implemented more than 20 hours per week, begun early in life, prior to the age of four, produces large gains in development and reduces the need for special services later in life (Smith, 1999). The National Research Council (2001) recommends between 25 and 40 hours a week for optimal results.

Such intensive packages, however, can be impractical and expensive for families. For example, a young person may be in school Monday to Friday and therefore a 40 hour programme would simply not be appropriate. Young children may find it far too difficult to be able to engage for 40 hours across a week. It is also vital to bear in mind that ultimately ABA therapy is often delivered in the home - we therefore need to be cautious that a programme of support is not impacting on family life by appearing invasive.

There may be options for families to secure funding through the local authority for their son or daughter for an ABA programme. If you have a social worker, it would be useful to discuss your options with them. Having a robust and comprehensive Education, Health, and Care Plan (EHCP) for your son or daughter will help.

However, a well-run programme that might be less “intensive” in terms of number of hours per week, can still achieve socially significant change that makes meaningful improvements to a young person’s and family’s life. We understand that financially and practically, 40 hours a week may be far too intensive a programme to sustain. Instead, an ABA programme should be on a case-by-case basis in terms of number of hours per week based on assessment conclusions and discussions with primary caregivers. Anything implemented must work for the entire family.

Hopefully this article has provided you with a clearer understanding of how ABA therapy can help your loved one with autism, as well as clarifying some common myths surrounding ABA.

If you would like to find out more about ABA in general, or would like to know how Beam can help someone you know with autism, please get in touch.

Cormac Duffy, Registered Manager

020 3886 0640

contact@beamaba.com